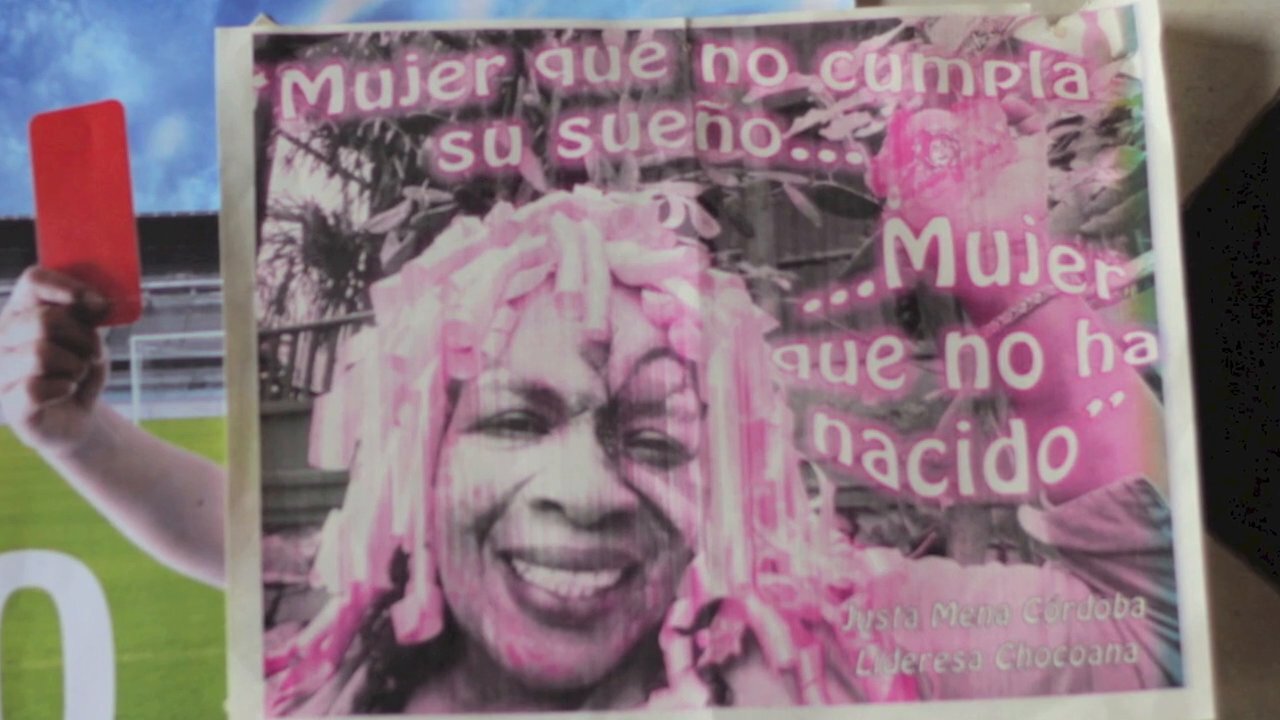

Justa Mena

El relato de Justa Mena, una mujer fuerte y decidida, es un testimonio de lucha y superación en medio de adversidades. Criada en una familia numerosa en el Atrato, Colombia, Justa Mena enfrentó las complejidades de un hogar marcado por la escasez de recursos. Sin embargo, su determinación y amor por sus hijos la llevaron a trazar un camino de éxito y transformación.

Desde una edad temprana, Justa Mena enfrentó desafíos, desde la separación de sus padres hasta la necesidad de trabajar lejos de su hogar para sobrevivir. Con valentía y sacrificio, construyó un futuro para sí misma y sus cinco hijos, priorizando su educación y bienestar.

A través de años de esfuerzo y sacrificio, Justa Mena logró educar a sus hijos y proporcionarles un futuro prometedor, desafiando las expectativas sociales y culturales arraigadas en su comunidad. Su dedicación como madre y líder comunitaria resonó en su compromiso con la igualdad de género y la justicia social, enfrentando obstáculos en una sociedad patriarcal para garantizar la inclusión y el empoderamiento de las mujeres.

Sin embargo, su viaje estuvo marcado por la adversidad, incluyendo el diagnóstico de cáncer avanzado. A pesar de ello, su fe inquebrantable y el apoyo de sus seres queridos le dieron fuerzas para seguir adelante, inspirando a otros a enfrentar los desafíos con valentía y esperanza.

El relato de Justa Mena es un recordatorio conmovedor de la resiliencia humana y el poder del amor y la determinación para superar cualquier obstáculo en el camino hacia una vida plena y significativa.

Transcripción

(0:07) Mi nombre es Justamena y quiero contar mi historia, mis experiencias que tengo tenido en la vida,

(0:18) mis logros y mis dificultades. Soy la cuarta hija de nueve hermanos.

(0:26) El nombre de mi madre era Ana Silveria Cordo, y mi padre Pilar Mena

(0:30) Tuvieron nueve hijos. Somos dos mujeres y siete hombres. Mi padre era un hombre muy popular aquí en el Atrato.

(0:39) Era un hombre que siempre tení cuatro mujeres, al público, como dicen aquí.

(0:47) Y de esas cuatro mujeres, había muchos niños. Dejó con vida a 30 niños cuando murió.

(0:56) Somos hermanos muy unidos,una familia muy unida.

(1:01) Estamos en el Apartadó, Turbo, Cali. Estamos en casi toda Colombia.

(1:10) Pero dondequiera que estemos, estamos mirando uno para el otro. Hay un hermano que es muy especial.

(1:18) Es el cabeza de familia. Vive en el Huila. (1:22) Y él es quien nos mantiene todos juntos.

(1:26) Porque, como él dice, la familia es así. El padre y la madre tienen que quedarse juntos hasta el final.

(1:32) Porque ese es el ejemplo que le damos a nuestros hijos. Mi padre era un hombre que, ya que tenía tantos hijos

(1:39) y éramos de muy pocos recursos, él no educó a los niños mucho. No tuvieron la oportunidad de estudiar, como nuestros hijos.

(1:49) Con sus cuatro mujeres que mantuvo, ellos se entendían muy bien, se llevaban bien muy bien.

(1:56) Ellos compartieron. Los niños los criaron a todos juntos. No había preferencia ni para uno ni para el otro.

(2:04) Parecía que todos éramos de una sola madre. Para que esa familia se entendiera tanto

(2:11) que cuando mi padre murió, continuamos el legado de unidad. Mi padre era un hombre de mucha experiencia.

(2:23) Fue un hombre que, a pesar de las dificultades tenia con las mujeres, porque era muy mujeriego, era muy responsable.

(2:32) Responsabilidad en el sentido de criar a sus hijos. Estaba muy pendiente de todos sus hijos.

(2:41) Aquí en el Chocó el poder prevalece sobre los hombres y él siempre fue la última palabra en el casa.

(2:49) Él fue quien puso las reglas. Él fue quien dijo lo que estaba hecho y lo que no se hizo.

(2:55) En mi vida personal comencé a cambiar esa estructura. En mi casa hablamos con mi pareja.

(3:03) Acordamos lo que íbamos a hacer con los recursos económicos como educariamos a los niños.

(3:11)Estábamos cambiando toda esa historia, toda esa tradición que trajo mi familia.

(3:19) Y hoy mis hijos son un ejemplo de que le di una educación diferente. Tienen sus casas, respetan a sus mujeres, todos tienen su pareja.

(3:32) Entonces ese es un ejemplo de lo que hicieron no seguir esa cultura y esas costumbres que ha traido del Chocó

(3:39) Es muy importante resaltar todo lo que mi madre vivió. Ella sufrió mucho.

(3:46) Mi madre tuvo que alejarse de mi padre por un tiempo. Era muy joven.

(3:52) Trabajé mucho porque me quedé con una tía y sufrí mucho. Desde pequeña he sufrido bastante.

(4:00) He pasado por mucho trabajo. Mi lucha ha sido incansable por seguir adelante, por ser alguien, por superarme, por servir a la gente.

(4:11) Cuando tenía 15 años vine de mi pueblo, que se llama San Roque, a estudiar aquí en Quibdó.

(4:22) Lo hice hasta quinto grado. Y de ahí pasé a trabajar en Medellín, en una casa familiar. Después de trabajar un año en Medellín, fui a Bogotá.

(4:35) Trabajé allí durante un año y un medio. No me quedé en Bogotá por el frío.

(4:41) Me fui a trabajar a Cali. Trabajé allí durante tres años. Allí tuve mi primer hijo. Me encontré con amigo del Choco. Nos juntamos, como se dice, y yo tuve mi primer hijo.

(4:57) Después de tener mi primer hijo, ambos empezó a trabajar allí. Y no nos quedamos allí porque siempre extrañé nuestra tierra.

(5:04) Chocó es una tierra que uno nunca olvida. Así que volvimos con nuestro primer hijo al Chocó.

(5:11)Y nos fuimos a la finca.Porque allí, en San Roque, en mi pueblito, tengo mi pequeña tierra de herencia que mi padre me dejó.

(5:21) Estábamos produciendo, estábamos trabajando. Tuvimos cuatro hijos más. Tengo cinco hijos. Soy madre de cinco hijos.

(5:29) Una mujer y cuatro niños. Y esos cinco niños, después de terminar la primaria, allá en San Roque, necesitaban escuela, secundaria y universidad.

(5:41) Y no había manera de darles esa educación. Entonces vine aquí, me mudé aquí para Quibdó por la educación de mis hijos.

(5:50) Y luego tuve que trabajar aquí en Cocomacía as a director. Y con esa producción que dio el ser directora, yo eduqué a mis hijos.

(6:01) Los metí en becas que existen aquí, de un convenio universitario con Cocomacía.

(6:07) Ingresé a mis hijos a la universidad. Fueron dos los que envié al Tolima, estudiar todo lo que es agro.

(6:14) Le debo mucho a esta organización. Entonces eso me llena de mucha orgullo, que durante esta lucha que he tenido tuve en este proceso,

(6:24) logré conseguir mis hijos educados. Mis hijos son gente humilde. Vienen del campo y son muy justos. Me aman mucho.

(6:35) Ellos me cuidan. Me tratan muy bien. ¿Qué quiero? Que conozcan el trabajo y la lucha que he llevado. Soy madre, cabeza de familia.

(6:48) Con el padre de mis hijos nos separamos. Hace 16 años. Tuve que luchar desde entonces con mis hijos, para sacarlos adelante.

(7:00) Fue una lucha muy, muy, muy dura,porque en cualquier caso hay que tomar cuidado de tus hijos.

(7:07) Siempre necesitas un padre que te ayude. En educación. Mis hijos terminaron su educación bajo mi responsabilidad.

(7:18) Él, ya no respondía a la educación. Hoy mis hijos están trabajando. Estoy descansando en casa.

(7:28) Vengo aqui a la organizacion para continuar aportando, porque todavía me siento animado a seguir lucha.

(7:37) Pero mis hijos están a cargo de mí. Entonces ese es un logro muy importante para una madre, ver que una luchaba e invirtió,

(7:48) dio su vida por sus hijos y que hoy ella está recibiendo esa recompensa.

(7:54) En el proceso organizativo ha sido muy difícil para mi. En el año 2000 fui elegido coordinador de el área de género.

(8:04) Y desde entonces, he tenido una muy lucha difícil, porque ésta es una organización,

(8:09) Que es una organización mixta, donde somos hombres y mujeres. Pero aquí en el Chocó hay una situación muy cultura patriarcal radical.

(8:19) Las mujeres no tienen el espacio ni la facilidad que tienen los hombres. Siempre son hombres.

(8:30) Las mismas mujeres siempre eligen a los hombres. Entonces no existe una política de igualdad en el organización.

(8:40) ¿Qué hemos hecho en el área de género? para garantizar que las mujeres estén incluidas?

(8:46) Hemos creado escuelas para que estos espacios son vistos. Las mujeres necesitan recibir formación, tenemos que ser conscientes de sus derechos para que podemos ejercitarlos.

(9:03) Porque por falta de conocimiento, lo mismo las mujeres a veces no asumen los espacios.

(9:09) Sigo luchando para que las mujeres sean en estos espacios. Ya tengo muchos problemas de salud. Hace tres años me diagnosticaron cáncer. Y está muy avanzado. Lo tengo muy avanzado.

(9:27) Ya tengo varios órganos afectados. Pero estoy con Dios. Es Dios quien decide qué hacer conmigo. Tengo fe en que seguiré luchar.

(9:41) Quiero agradecer a todos mis amigos, mi familiares que han estado conmigo incondicionalmente, mi niños, a todos aquellos que me han apoyado en este difícil momento que estoy viviendo.

(9:57) Gracias a Dios y a ellos estoy aún viva. Porque la lucha la hemos hecho juntos mi enfermedad.

(10:06) No me han dejado solo en ningún momento. Eso me ha dado fuerzas para continuar.

(10:09) Quiero decirle a la gente que tiene estas enfermedades terminales, como la que tengo, para no estar afligido, seguir luchando, luchar por vida y acoger a Dios.

(10:28) Dios es quien todo lo puede. Y Dios es el que sabe cuando está destinado que uno sea o sea no en este mundo.

(10:38) En cuanto a mi hija, quiero agradecer mucho, sobre todo porque mi hija sufrió mucho. Ha tenido que sufrir.

(10:51) Pasamos dos años en Medellín con ella. Y ella tuvo que vivir todo lo que yo he sufrido.

(10:57) Me hicieron tantas cirugías que ella dijo: “Mamá, siento que me la van a matar aquí.

(11:05) Hicieron un año de quimioterapia y la quimioterapia fue súper fuerte. Estaba totalmente drogada.

(11:13) quiero como un agradecimiento especial a ella. Mis hijos me apoyaron mucho moral, espiritualmente, económicamente.

(11:22) He tenido todo el apoyo posible de mis amigos, mis familiares, mis compañeras de trabajo.

(11:28) Les agradezco mucho porque tienen toleraron mi enfermedad, me han sanado. Por eso les estoy muy agradecida.

Translation

(0:07) My name is Justa Mena, and I want to tell my story, my experiences that I have had in life, my achievements, and my difficulties. I am the fourth daughter of nine siblings.

(0:26) My mother's name was Ana Silveria Cordo, and my father's Pilar Mena. They had nine children. We are two women and seven men. My father was a very popular man here in the Atrato.

(0:39) He was a man who always kept four women, public, as they say here. And of those four women, there were many children. He left 30 children alive when he died. We are very close brothers, a very close family.

(1:01) There are some in Apartado, Turbo, in Cali. We are in almost all of Colombia. But wherever we are, we are looking out for each other.

(1:15) There is a brother who is very special. He is the head of the family. He lives in Huila. And he is the one who brings us all together because, as he says, the family is like that.

(1:29) The father and the mother have to stay together until the end. Because that is the example we give to our children. My father was a man who, since he had so many children,

(1:39) and we were of very few resources, he did not educate the children much. His children did not have the opportunity to study. With the four women that he kept,

(1:51) they understood each other very well, and they got along very well. They shared. The children raised them all together. There was no room for either one or the other.

(2:04) It seemed that we were all one mother. So that family understood each other so much that when my father died, we continued the legacy of unity.

(2:17) My father was a man of a lot of experience. He was a man who, despite the difficulties he had with women, because he was very womanizer, he was very responsible.

(2:32) Responsibility in the sense of raising his children. He was very aware of all his children. Here in Chocó, power prevails over men

(2:45) and he was always the last word in the house. He was the one who set the rules. He was the one who said what was done and what was not done.

(2:55) In my personal life, I began to change that structure.In my home, we talked with my partner. We agreed what we were going to do with the economic resources,

(3:09) how we were going to educate the children. We were changing all that history, all that tradition that my family brought.

(3:19) And today my children are an example that I gave a different education. They have their homes, they respect their women, they all have their partner.

(3:32) So that is an example that they did not follow that culture and those customs that Chocó has brought.

(3:39) It is very important to highlight everything that my mother lived. She suffered a lot. My mother had to move away from my father for a while.

(3:50) I was very young. I did a lot of work because I stayed with an aunt. And I suffered a lot.

(3:58) Since I was little, I have suffered a lot. I have gone through a lot of work. My struggle has been tireless for moving forward, for being someone, for overcoming myself,for serving people.

(4:11) When I was 15 years old, I came from my town, which is called San Roque, to study here in Quibdó. I did until fifth grade. And from there I went to work in Medellín,in a family home.

(4:30) After I worked for a year in Medellín, I went to Bogotá. I worked there for a year and a half.

(4:38) I did not stay in Bogotá because of the cold. I went to work in Cali. I worked there for three years. There I had my first child.

(4:46) I met a Chocó friend. We got together, as one says, and I had my first child. (4:55) After I had my first child, we both started working there.

(5:00) And we did not stay there because we always missed our land. Chocó is a land that one never forgets. So we came back with our first child here, to Chocó.

(5:11) And we went to the farm. Because there, in San Roque, in my town, I have my little land of inheritance that my father left me.

(5:21) We were producing, we were working. We had four more children. I have five children. I am a mother of five children.

(5:29) One woman and four boys. And those five children, after they finished elementary school, there in San Roque, they needed school and high school and the university.

(5:41) And there was no way to give them that education. So I came here, I moved here to Quibdó for the education of my children. And then I had to work here in Cocomacía as a director.

(5:55) And with that production that the director gave me, I educated my children. I got them into scholarships that exist here, from a university agreement with Cocomacía.

(6:07) I got my children into the university. There were two that I sent to Tolima, (6:12) to study everything that is agro. I owe a lot to this organization.

(6:17) So that fills me with a lot of pride, that during this struggle that I have had in this process, I managed to get my children educated.

(6:28) My children are humble people. They come from the countryside, and they are very just. They love me a lot. They take care of me. They treat me very well.

(6:40) What do I want? That they know the work and the struggle that I have carried. I am a mother, head of the family. With the father of my children, we separated 16 years ago.

(6:52) I had to fight from then on with my children, to get them through on their own. It was a very, very, very hard struggle, because in any case, you have to take care of your children.

(7:07) You always need a father to help you in education. My children finished their education under my responsibility. He no longer responded to education.

(7:22) Today, my children are working. I am resting at home. I come here to the organization to continue contributing, because I still feel encouraged to continue fighting.

(7:37) But my children are in charge of me. So that is a very important achievement for a mother, to see that one fought and invested, gave her life for her children, and that today she is receiving that reward.

(7:54) In the organizational process, it has been very difficult for me. In 2000, I was elected as coordinator of the gender area. And since then, I have had a very difficult struggle, because this is an organization, which is a mixed organization, where we are men and women.

(8:13) But here in Chocó, there is a very radical patriarchal culture. Women do not have the space or the facility that men have. It is always men.

(8:30) The same women always elect men. So there is no equality policy in the organization. What have we done in the gender area to ensure that women are included? We have created schools so that these spaces are seen.

(8:52) Women need to be trained, we need to be made aware of their rights so that we can exercise them. Due to lack of knowledge, the same women sometimes do not assume the spaces.

(9:09) I continue to fight for women to be in these spaces.I already have many health problems. Three years ago, I was diagnosed with cancer. And it is very advanced.

(9:25) I have it very advanced. I already have several affected organs. But I am with God. It is God who decides what to do with me. I have faith that I will continue to fight.

(9:41) I want to thank all my friends, my relatives who have been with me unconditionally, my children, all those who have supported me in this difficult moment that I am living.

(9:57) Thanks to God and them, I am still alive. Because we have done the fight together with my illness. They have not left me alone at any time.

(10:09) That has given me strength to continue. I want to tell people who have these diseases, like the one I have, not to be afflicted, to keep fighting, to fight for life, and to welcome God. (10:28) God is the one who can do everything. And God is the one who knows when it is destined that one is or is not in this world.

(10:38) As for my daughter, I want to thank her very much, especially, because my daughter has suffered a lot. She has had to suffer.

(10:51) We spent two years in Medellín with her. And she had to live everything that I have suffered. They did so many surgeries that she said, Mom, I feel like they are going kill you. (11:05) They did a year of chemo, and the chemo was super strong. I was totally doped. I want to give her a very special thank you.

(11:17) My children supported me a lot morally, spiritually, and economically. I have had all the possible support from my friends, my family members, my coworkers.

(11:28) I thank them very much because they have tolerated my illness, they have healed me. So I am very grateful to them.

Luz Adonis Mena

El testimonio de Luz Adonis Mena Becerra refleja la lucha y la resiliencia de una mujer que enfrentó desafíos desde una edad temprana. Criada en la comunidad de Altagracia, Río Munguido, Luz perdió a su madre a los tres meses y fue criada por una tía. A pesar de las dificultades, logró completar la secundaria con el apoyo de un tío, pero se enfrentó a obstáculos para acceder a la universidad debido a limitaciones económicas.

Después de un desplazamiento masivo que la obligó a trasladarse a la ciudad en busca de oportunidades, Luz se involucró en un proceso organizativo que le permitió tomar conciencia de la importancia del trabajo comunitario. Junto con otras mujeres, reconoció la necesidad de una mayor representación y participación en la toma de decisiones dentro de la organización.

Motivada por esta visión, Luz y sus compañeras buscaron establecer una comisión de género para garantizar que los derechos de las mujeres fueran reconocidos y respetados, y que pudieran participar activamente en todos los aspectos del proceso organizativo. Su llamado a las compañeras para que se unan a capacitaciones y reclamen sus derechos refleja su compromiso con la igualdad y el empoderamiento de las mujeres en la comunidad.

El relato de Luz es un testimonio inspirador de perseverancia, solidaridad y determinación en la lucha por la justicia y la equidad de género, destacando la importancia de la educación, la participación comunitaria y el respeto de los derechos humanos para construir un futuro más justo y pacífico para todos.

Transcripción

(0:06) Mi nombre es Luz Adonis Mena Becerra, vengo de Rio Munguido, en una comunidad llamada Altagracia.

(0:13) Mi vida fue muy dura, porque cuando tenía tres meses mi madre murió. Y allí me quedé con una señora, una tía de mi madre.

(0:24) Ella fue quien me crió, me dio los primeros estudios en la comunidad. Y ella no tenía como darme estudio aquí en la ciudad de Quildó, para el bachillerato.

(0:33) Me entregó a una señora para que estudiara y yo la ayudaba con las tareas del hogar. Como sabemos, estas mujeres siempre cogen a las chicas que vienen del campo y les prometen que colaborarán.

(0:49) Pero no, todo fue diferente. Cuando llegué aquí, ella me obligaba a hacer las tareas del hogar, no me puso en la escuela.

(0:57) Y últimamente mi madre vio que yo estaba pasando por tanto trabajo y me llevó de nuevo a la comunidad. De allí me envió a vivir con un tío.

(1:08) Me ayudó hasta que terminé la secundaria. Después de terminar la escuela secundaria, mi tío no pudo llevarme a la universidad.

(1:15) Cuando regresé a la ciudad, regresé a la comunidad. Yo estaba allí haciendo el trabajo en la montaña que siempre hace la gente en las comunidades.

(1:27) Y luego hubo un desplazamiento masivo desde Río Munguidón. Desplazamos a todas las comunidades donde teníamos que venir a trabajar a la ciudad. Porque si no te daban de comer, no comías.

(1:45) Todo era limitado. Había que pagar alquiler. Y a partir de ahí fue el proceso organizativo.

Un colega que venía mucho estuvo involucrado en el proceso organizativo.

(1:58)Ella me invitó a un taller que había allí. Y a partir de ahí tomé conciencia y me involucré. A partir de ahí vi que en esa organización se trabajaba para el trabajo de las comunidades.

(2:09) que estaban a orillas del río Atrato, a orillas de los ríos. Y a partir de ahí fue que nosotras, las mujeres,porque la organización nació entre hombres y mujeres,

(2:23) y las mujeres se involucraron en todo lo que tenía que ver con el proceso de mujeres. Tomamos una decisión, dijo un colega,

(2:32) Las mujeres siempre hemos estado en el proceso organizativo, siempre hemos estado a cargo de la logística, pero nunca estamos donde se toman las decisiones.

(2:42) Fue entonces cuando el colega dijo: Tenemos que luchar para ver si creamos una comisión de género donde se reflejan los derechos de las mujeres,

(2:54) donde se toman las decisiones, porque no podemos estar en la logística todo el tiempo, sólo porque, aunque lo estamos implementando,

(3:03) Todavía hay mujeres que desconocen sus derechos. y seguir usándolos siempre para estar en la cocina.

(3:11) Y eso es lo que estamos buscando, que las mujeres aprendan a reclamar sus derechos.

(3:18) Mi llamado es para las compañeras, que cuando nos inviten a la capacitación, que no seamos ajenos a las invitaciones que les hacemos presentes,

(3:28) porque esos entrenamientos son muy útiles para la vida personal, para que uno aprenda a reclamar sus derechos,

(3:36) porque si no participamos, nunca conoceremos sus derechos, e invitarlos para que vivamos en convivencia pacífica,

(3:45) en su comunidad, con sus hijos, que no maltratemos a los niños, que formemos bien a los niños, que les demos buenos consejos, para que los niños estén al servicio de nuestro país.

Translation

(0:06) My name is Luz Adonis Mena Becerra, I come from Río Munguido, a community called Altagracia.

(0:13) My life was very hard, because when I was three months old, my mother died. And there I stayed with a lady, an aunt of my mother.

(0:24) She was the one who raised me, she gave me the first studies in the community. And she didn't have money to help me study here in the city of Quildó, in high school.

(0:33) She gave me to a lady to study and I helped her with the housework. As we know, these women always take the girls who come from the countryside and promise them that they will collaborate.

(0:49) But no, everything was different. When I got here, she made me do her housework, she didn't put me in school.

(0:57) And lately, my mother saw that I was going through so much work, she took me back to the community. From there, she sent me to live with an uncle. He helped me until I finished high school.

(1:11) After I finished high school, my uncle couldn't get me into college. When I came back to the city, I went back to the community.

(1:20) I was there doing the work in the mountains that people always do in the communities.

(1:27) And then, there was a massive displacement from Río Munguidón. We displaced all the communities where we had to come to the city to work.

(1:40) Because if they didn't give you a meal, you didn't eat. Everything was limited. You had to pay rent. And from there, it was the organizational process.

(1:53) A colleague who came a lot was involved in the organizational process. She invited me to a workshop that was there.

(2:00) And from there, I became aware and I got involved. From there, I saw that in that organization, the work was done for the work of the communities that were on the banks of the Atrato River, on the banks of the rivers.

(2:15) And from there, it was that we, the women, because the organization was born by men and women, and the women were involved in everything that had to do with the women's process.

(2:28) We made a decision, a colleague said, we, the women, have always been in the organizational process, we have always been in charge of the logistics, but we are never where the decisions are made.

(2:42) That's when the colleague said, we have to fight to see if we set up a gender commission where the rights of women are reflected, where the decisions are made, because we can't be in the logistics all the time,

(2:58) only because, even though we are implementing that, there are still women who do not know their rights and always continue to use them to be in the kitchen.

(3:11) And that is what we are looking for, that women learn to claim their rights. My call is for the female colleagues, that when they invite us to the training,

(3:23) that we are not alien to the invitations that we make them present because those trainings are very useful for one's personal life,

(3:33) for one to learn to claim their rights, because if we don't participate, we will never know their rights, and to invite them so that we live in peaceful coexistence,

(3:45) in their community, with their children, that we do not mistreat the children, that we train the children well, that we give them good advice, so that the children are the service of our country.

Rubiela Cuesta

El relato de vida de esta mujer, cuyo nombre no conocemos, es un testimonio conmovedor de resiliencia, perseverancia y dedicación en medio de las adversidades. Desde una edad temprana, se vio enfrentada a desafíos significativos, como casarse a los 14 años y criar a sus hijos sola tras la trágica muerte de su esposo.

A lo largo de más de 25 años, ha estado involucrada en procesos comunitarios, mostrando un profundo compromiso con su comunidad y con el empoderamiento de las mujeres. A pesar de los tropiezos y dificultades en su camino, ha desempeñado roles destacados como madre, líder comunitaria y defensora de los derechos de las mujeres.

Su experiencia demuestra la importancia del trabajo colectivo y la solidaridad en la superación de obstáculos. A través de su participación activa en diferentes actividades comunitarias, ha logrado no solo sacar adelante a su familia, sino también influir positivamente en su entorno y en la vida de otras mujeres.

Su mensaje es uno de inspiración y aliento para otras mujeres que puedan enfrentar circunstancias similares. Les insta a no tener miedo de participar en procesos de empoderamiento y desarrollo comunitario, y a reconocer el valor y la capacidad de las mujeres para liderar y contribuir de manera significativa a la sociedad.

En última instancia, su historia resalta la importancia de la resiliencia, la determinación y la solidaridad en la búsqueda de un mundo más justo y equitativo para todas las personas, especialmente para las mujeres que han sido históricamente marginadas y subestimadas.

TRANSCRIPT

(0:07) Hace más de 25 años vengo metida en los procesos comunitarios. Me gusta, me gusta aprender con las comunidades, con la gente.

(0:17) Me casé de edad de 14 años. Mi esposo era Paculteño, hijo único de una señora María Cabrera.

(0:27) En ese hogar tuve cinco hijos. Se me murió una de un añito, tengo cuatro, tres mujeres y un niño.

(0:36) Fui muy felizmente casada por el señor Ezequiel Monroy. Pero por cuestiones del destino a veces la gente quiere cambiar la forma de vivir

(0:49) porque de pronto uno cree que donde está, está echando mal, o que si se va para otro lugar después se le cambia la vida.

(0:58) Se fue para Zaragoza buscando mejor nivel de vida. Y allá se enredó con una señora que era la mujer del dueño,

(1:09) del trabajo donde él estaba y allá lo mataron. Hace 25 años de eso, me tocó criar los hijos sola porque él se fue por allá y allá lo mataron.

(1:20) Los hijos prácticamente no los conocieron, a mí me tocó luchar sola con la familia. Soy una mujer que me gusta mucho mi trabajo individual.

(1:30) Me gusta tener mis cosas y con mi esfuerzo saqué mi familia adelante gracias a Dios. Trabajando honestamente, mi mamá era muy aguerrida.

(1:43) Me tocó irme hasta el Nariño a buscar mejor calidad de vida para poder sacar los pelados adelante porque ya están en el colegio, y aquí en Quibdó me daba muy difícil.

(1:52) Fui madre comunitaria, presidenta de acción comunal en mi comunidad, representante legal por varios periodos.

(2:02) Y es una experiencia muy bonita cuando uno como persona emprende tantas actividades que las otras personas están ahí observando y mirando.

(2:14) Bueno, ¿y esta por qué lo hace? ¿Cómo lo hace? ¿Por qué está en todo? Y siempre lo tienen en cuenta.

(2:19) A veces la facilidad de uno entregarse a las cosas, que la gente mira la espontaneidad, eso lo ayuda a uno a seguir multiplicando el ejercicio de estar en todo.

(2:31) Porque a veces uno ni quiere estar en las cosas y la gente mira la espontaneidad y no, venga, llamemos a fulana.

(2:38) Y entonces eso me hizo ir creciendo, porque la gente siempre miraba, yo nunca dije no, siempre dije sí.

(2:45) Es bueno en muchos sentidos, pero a veces también tiene sus dificultades, porque hay personas que sienten celos.

(2:52) Alrededor de uno sienten celos. Familias, amigos, vecinos.

(2:56) ahí es que está pues que , esté bozo pues que, toca pero ese ejercicio de aprendizaje y de conocimiento que uno va adquiriendo,

(3:08) eso le va dando un espacio, un empoderamiento, un reconocimiento a nivel comunitario, a nivel de la familia, a nivel de la sociedad.

(3:21) Porque dicen, no, es que aquí la que está en capacidad de tal cosa es fulana de tal.

(3:27) Y eso también me ayudó para poder ser una madre ejemplar, sacar a mi familia adelante. (3:32) Hoy en día mis hijas son universitarias.

(3:34) No me arrepiento de pronto no haber tenido otro hogar en el lazo del tiempo que quedé viuda.

(3:42) He tenido tropezones en mi vida, dificultades. Hay momentos que me ha dado ganas de no estar, de irme, que nadie se dé cuenta.

(3:53) Pero yo creo que la mejor, el mejor legado que uno deja a la familia y a los amigos es la resistencia, el querer, esa espontaneidad, esa dedicación, esa honestidad

(4:12) de hacer las cosas sin que la gente mire en uno esa suspicacia, esa galla de querer estar ahí

(4:20) porque esto me quedo con esto o me lo llevo. Todo ese bagaje, esa huella de camino, de aprendizaje, de experiencia, de conocimiento.

(4:32) Eso uno le deja a los hijos, a las amigas. Eso va uno acumulando, se va enriqueciendo uno.

(4:41) Uno dice al final, no, no perdí el tiempo, valió la pena estar en todo. Ese es uno de los puntos que hoy en día me siento feliz, me siento realizada

(4:55) porque lo que me gusta todavía lo sigo haciendo, lo estoy demostrando que lo hago bien.

(4:59) Mi familia se siente contenta, me apoyan en algunas cosas, que a veces me reclaman porque no les dedico mucho tiempo.

(5:09) Y para las compañeras que están a mi lado, que trabajamos juntas, también aprendo mucho de ellas, ellas aprenden de mí.

(5:19) Y el motivo de continuar en esta lucha es porque para las comunidades negras y por qué no decir para el mundo entero, las mujeres no nos miraban

(5:33) como una persona útil en la sociedad, únicamente nos miraban como una parte receptora y para producir, para tener los hijos.

(5:44) Entonces, esto de estar hoy en día que habemos tantas mujeres líderes, líderesas,

(5:51) doctoras, abogadas, alcaldesas, es una lucha, un trabajo que se ha venido haciendo hace mucho tiempo porque el machismo y el patriarcado que nos han enseñado

(6:05) que la mujer es para la casa y el hombre para la calle, que la mujer es para tener los hijos y criarlos,

(6:12) no nos daban la oportunidad que estuviéramos en los espacios donde dan las tomas de decisión.

(6:17) Siempre la mujer callaba, siempre la mujer obedecía, siempre la mujer escuchaba, pero nunca opinaba ni tampoco decidía.

(6:27) Y hoy en día por medio de todos estos procesos, de estas capacitaciones que hemos estado dentro de sus organizaciones, en sus comunidades,

(6:34) ya tenemos esa autonomía y ese derecho de opinar, decidir y que eso nos escuche lo que decimos y que se tenga en cuenta la opinión de las mujeres.

(6:46) Yo le doy gracias a Dios que, como siempre me gustó estar metida en los procesos desde que me casé, hoy en día pues tengo como ese conocimiento,

(6:59) ese bagaje, esa experiencia para decirles a las compañeras que no les gusta, que todavía les da miedo, que les parece que esto es de loco,

(7:08) que no es tan importante estar metida en todo, que es mejor estar en casa. Las invito, que sí es importante aprender y estar en los espacios, en los procesos.

(7:22) Le pedí a Dios que después que perdí a mi esposo, me diera la oportunidad de conseguirme una pareja

(7:31) que me pudiera entender con él, estar bien con él, pero me daba miedo en su momento por las hijas,

(7:39) porque tuve mi hija y tres hijas mujeres, entonces eso me condenó a estar sola hasta hoy.

(7:45) No tuve otro hogar. Siempre me dio miedo por ello, porque me daba miedo colocarles padrastros a los hijos. (7:53) Me castigué, yo misma me castigué.

(7:56) No me di la oportunidad de estar con otra persona así. Es mentira que las mujeres apenas son buenas para parir, es mentira.

(8:06) Las mujeres somos buenas en todo, en todo porque está demostrado. Somos buenas mamás, somos buenas esposas, somos buenas profesionales, somos dedicadas.

(8:18) Entonces es mentira que somos brutas, es mentira que somos feas, es mentira que servimos apenas,

(8:23) que eso no sabemos hacer nada, es mentira. La mujer todo lo hace bien, todo lo hace bonito, elegante.

(8:30) Y cuando se dedica, y la mujer es muy inteligente, porque las mujeres siempre planificamos y calculamos bien las cosas.

(8:42) Y siempre pensamos en los demás. Las mujeres siempre piensan cómo hago para colaborar con el vecino,

(8:48) cómo hago para colaborarle acá al primo, cómo le colaboro a la tía. Las mujeres siempre estamos ahí en ese lugar.

(8:55) Entonces hemos llamado a las otras compañeras de otros países que escuchen esta grabación,

(9:02) que escuchen este mensaje, que sí, las mujeres pasamos trabajo. Tenemos una historia de vida, de lucha, de dedicación por los hijos, por la familia, por la comunidad,

(9:14) porque casi todas pasamos por eso. Somos madres, cabezas de familia, no tenemos un esposo, no tenemos a nadie que nos ayude a criar los hijos.

(9:22) No siempre los sacamos adelante solas. Las invito a todas las compañeras del proceso y las que no están en el proceso que vengan.

(9:30) Dicen que se acerquen. Esto nos da una estabilidad familiar y una estabilidad emocional y personal.

Traducción

(0:07) I have been involved in community processes for more than 25 years. I like it, I like learning with the communities, with the people.

(0:17) I got married when I was 14 years old. My husband was Paculteño, the only son of a woman María Cabrera.

(0:27) In that home I had five children. A one-year-old died, I have four, three women and a child.

(0:36) I was very happily married by Mr. Ezequiel Monroy. But for reasons of destiny, sometimes people want to change the way they live.

(0:49) because suddenly you believe that where you are, you are doing something wrong, or that if you go to another place later your life will change.

(0:58) He left for Zaragoza looking for a better standard of living. And there he got involved with a woman who was the owner's wife,

(1:09) from the work where he was and they killed him there. 25 years ago, I had to raise the children alone because he went there and they killed him there.

(1:20) The children practically did not know them, I had to fight alone with the family. I am a woman who really likes my individual work.

(1:30) I like to have my things and with my efforts I brought my family forward, thank God. Working honestly, my mother was very brave.

(1:43) she I had to go to Nariño to look for a better quality of life to be able to move forward because they are already in school, and here in Quibdó it was very difficult for me.

(1:52) I was a community mother, president of community action in my community, and legal representative for several periods.

(2:02) And it is a very nice experience when you as a person undertake so many activities that other people are there observing and watching.

(2:14) Well, and why does he do it? As it does? Why is it in everything? And they always take it into account.

(2:19) Sometimes the ease of surrendering to things, that people see spontaneity, that helps one to continue multiplying the exercise of being in everything.

(2:31) Because sometimes you don't even want to be involved in things and people look at spontaneity and no, come on, let's call so-and-so.

(2:38) And then that made me grow, because people always looked, I never said no, I always said yes.

(2:45) It is good in many ways, but sometimes it also has its difficulties, because there are people who feel jealous.

(2:52) They feel jealous around you. Families, friends, neighbors.

(2:56) That's where it is, well, it's just that, it's time for that exercise of learning and knowledge that one is acquiring,

(3:08) This gives them space, empowerment, recognition at the community level, at the family level, at the society level.

(3:21) Because they say, no, here the one who is capable of such a thing is so-and-so.

(3:27) And that also helped me to be an exemplary mother, to support my family. Today my daughters are university students.

(3:34) I don't suddenly regret not having had another home during the time I was widowed.

(3:42) I have had setbacks in my life, difficulties. There are moments that have made me want to not be there, to leave, that no one notices.

(3:53) But I believe that the best, the best legacy that one leaves to family and friends is resistance, love, that spontaneity, that dedication, that honesty.

(4:12) to do things without people seeing in you that suspicion, that pride of wanting to be there

(4:20) because I'll keep this or take it with me. All that baggage, that trace of the journey, of learning, of experience, of knowledge.

(4:32) One leaves that to the children, to the friends. One accumulates that, one becomes enriched.

(4:41) You say in the end, no, I didn't waste my time, it was worth being in everything. That is one of the points that today I feel happy, I feel fulfilled

(4:55) because I'm still doing what I like, I'm showing that I do it well.

(4:59) My family feels happy, they support me in some things, sometimes they complain to me because I don't dedicate much time to them.

(5:09) And for the colleagues who are by my side, who work together, I also learn a lot from them, they learn from me.

(5:19) And the reason we continue in this fight is because for the black communities and why not say for the entire world, women did not look at us

(5:33) as a useful person in society, they only looked at us as a receiving party and to produce, to have children.

(5:44) So, today there are so many women leaders,

(5:51) doctors, lawyers, mayors, it is a fight, a work that has been done for a long time because the machismo and patriarchy that we have been taught

(6:05) that the woman is for the house and the man for the street, that the woman is for having children and raising them,

(6:12) They did not give us the opportunity to be in the spaces where decision-making takes place.

(6:17) The woman was always silent, the woman always obeyed, the woman always listened, but she never gave her opinion nor did she decide.

(6:27) And today through all these processes, these trainings that we have been within their organizations, in their communities,

(6:34) We already have that autonomy and that right to give our opinion, decide and that they listen to what we say and that the opinions of women are taken into account.

(6:46) I thank God that, as always, I liked being involved in the processes since I got married, today I have that knowledge,

(6:59) that baggage, that experience to tell your colleagues that you don't like it, that it still scares them, that it seems crazy to them,

(7:08) that it is not so important to be involved in everything, that it is better to be at home.

(7:13) I invite you, it is important to learn and be in the spaces, in the processes. I asked God that after I lost my husband,

(7:26) to give me the opportunity to get a partner that I could understand him, be good with him, but I was scared at the time for the daughters,

(7:39) because I had my daughter and three daughters, so that condemned me to be alone until today.

(7:45) I had no other home. I was always afraid of it, because I was afraid of putting stepparents on my children.

(7:53) I punished myself, I punished myself. I didn't give myself the opportunity to be with another person like that.

(8:01) It is a lie that women are barely good at giving birth, it is a lie. Women are good at everything, at everything because it is proven.

(8:11) We are good mothers, we are good wives, we are good professionals, we are dedicated.

(8:18) Then it is a lie that we are brutes, it is a lie that we are ugly, it is a lie that we barely serve,

(8:23) That we don't know how to do anything is a lie. The woman does everything well, she makes everything beautiful, elegant.

(8:30) And when she is dedicated, and the woman is very intelligent, because women always plan and calculate things well.

(8:42) And we always think of others. Women always think about how I can collaborate with my neighbor,

(8:48) How can I help my cousin here, how can I help my aunt. Women are always there in that place.

(8:55) So we have called on the other colleagues from other countries to listen to this recording,

(9:02) Let them listen to this message, that yes, women have work.

(9:08) We have a history of life, of struggle, of dedication for children, for family, for the community,

(9:14) because almost all of us go through that.

(9:16) We are mothers, heads of families, we do not have a husband, we do not have anyone to help us raise children.

(9:22) We don't always get them through alone.

(9:24) I invite all the colleagues in the process and those who are not in the process to come.

(9:30) They say come closer.

(9:33) This gives us family stability and emotional and personal stability.

Banessa Rivas

El relato de Banessa nos sumerge en su trayectoria como miembro activo de la comunidad de Isla de los Rojas, en el municipio de Morindo, Antioquia, área influenciada por la Cocomacia. Desde su infancia, Banessa fue inspirada por su madre para involucrarse en los procesos comunitarios, asistiendo a reuniones y capacitaciones desde una edad temprana.

A lo largo de los años, ha participado activamente en diferentes actividades y talleres, encontrando gratificación en poder compartir conocimientos y experiencias con su comunidad. Destaca el papel fundamental de la Cocomacia en brindar apoyo y esperanza a las personas en momentos difíciles, lo cual considera una de las fortalezas de la organización.

En la actualidad, Banessa forma parte de la comisión de género de la Cocomacia, donde continúa contribuyendo a la defensa del territorio y promoviendo la participación de los jóvenes en los procesos comunitarios. Reconoce la importancia de preservar y transmitir los conocimientos ancestrales a las generaciones futuras, como una forma de enriquecer la identidad y la cultura de la comunidad.

A pesar de los desafíos y dificultades que enfrenta, Banessa encuentra fuerzas en su hijo de 4 años y en su pasión por su trabajo comunitario. Agradece a Dios por la oportunidad de poder trabajar y compartir con las personas, expresando su deseo de seguir aprendiendo y contribuyendo a su comunidad.

Su testimonio refleja el compromiso, la determinación y el amor por su comunidad, así como la importancia de trabajar en conjunto para alcanzar objetivos comunes. Banessa nos inspira a seguir adelante con esperanza y dedicación en la construcción de un futuro mejor para todos.

Carmen Navia

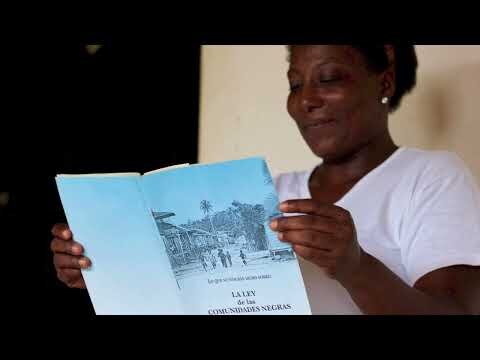

Carmen Navia comparte su experiencia como miembro activo de la comunidad de Tutunendo, zona 1, donde creció y completó su educación secundaria. Influenciada por la participación de su padre en los comités locales y en la defensa de los territorios, Carmen se involucró en el proceso organizativo de la Cocomacia.

Desde entonces, ha dedicado 17 años a este proceso, aprendiendo y fortaleciéndose como persona. Reconoce el impacto transformador que ha tenido en su vida, brindándole la oportunidad de defender el territorio y promover el respeto por los derechos de las comunidades.

Carmen destaca la importancia de la organización en la protección de los recursos naturales y en la defensa de los derechos de las mujeres. Se siente comprometida con el empoderamiento femenino y la promoción de la igualdad de género, impulsando a las mujeres a tomar decisiones y participar activamente en la vida comunitaria.

Su vínculo emocional con la Cocomacia es profundo, considerándola como su hogar y lugar de realización personal. Para Carmen, la organización representa la libertad de expresión, el respeto por los valores y derechos, y el compromiso con el progreso de su comunidad. Su testimonio refleja el poder del activismo comunitario para generar cambios positivos y empoderar a las personas para construir un futuro mejor.

Transcripción

(0:05) Yo soy Carmen Navia, soy de la comunidad de Tutunendo, de la zona 1, tengo 9 hermanos,

(0:17) dentro de los 9 yo soy la menor y allá en esa comunidad de Tutunendo terminé mi bachiller

(0:29) y luego me vine para acá a Quibdó a terminar los últimos dos años. Cuando terminé pues

(0:39) allá en Tutunendo se hablaba mucho de la Asia y existía unos consejos comunitarios,

(0:46) no era consejo comunitario sino comité local y mi papá me llevaba mucho a esas reuniones

(0:53) y se hablaba de la Asia, se hablaba de unos territorios y en el 99 pues a mí como que

(1:01) me fue gustando lo que él decía y él salía mucho a comisiones, yo me fui integrando por

(1:09) el tema y de un momento a otro me metí el proceso, me metí el proceso organizativo

(1:17) donde yo, mi vida ha cambiado mucho, en ese tiempo del 91 uno termina y estas inociones,

(1:30) a veces económicamente no tuve como seguir la universidad y desde ahí ya me metí a este

(1:37) proceso donde me ha enseñado tantas cosas, a ver la vida diferente, si yo no estuviera aquí

(1:46) en Cocomacia yo creo que mi vida sería diferente porque se me presentaron muchísimas oportunidades

(1:55) tanto buenas como malas también, entonces ya uno iba conociendo las amistades de aquí en la

(2:05) organización que era diferente a las otras amistades, la gente que no estaba metida pues

(2:11) como en la Asia y me fue interesando mucho la defensa de este territorio viendo que nosotros

(2:21) somos los que cuidamos el bosque, somos los dueños y como anteriormente venían las empresas, se metían

(2:31) a las comunidades sin permiso, iban sacando toda la madera y en el caso de mi pueblo allá en Tutuniendo

(2:40) también esas compañías venían unos paisas y eso cortaban madera en cualquier territorio y uno no

(2:50) tenía pues como, no había una ley ni había una autoridad uno como suspenderla, entonces ya con lo

(2:58) de la organización cuando ya nos metimos a los reglamentos pues hubo como paralizar eso y como

(3:07) nosotros podíamos defender esa madera, en estos momentos las cosas ya son muy diferentes

(3:16) porque ya contamos con una ley 70, tenemos unos reglamentos y hacemos cumplir nuestro

(3:27) derecho para que no se nos respete. Ya llevo 17 años de estar vinculada a todo este proceso y he

(3:40) aprendido a fortalecerme a ser una persona diferente, sigo aquí porque es la única organización que yo

(3:52) puedo estar libre, donde mis valores, mis derechos, aprendí a conocerlos y a respetarlos y me siento

(4:03) muy bien, es mi organización, le siento mucho amor por ella, siento que si yo llego aquí a Quibdó y no

(4:11) paso aquí a esta sede como que no fuera llegado aquí a Quibdó, entonces siento mucho amor por esta

(4:18) organización y también por el papel de las mujeres, de ser multiplicadora, de llevarle mensaje a ellas,

(4:28) de que no sigan más en ese papel de hechas de dama de casa, nosotros las mujeres también tenemos el

(4:36) derecho de salir, de conocer, de darnos nuestras propias decisiones, de llegar a las reuniones y

(4:45) opinar, no solamente llegar y quedarnos allá sentados sino salir adelante, porque si no,

(4:51) estamos totalmente volviéndonos atrás, por eso estoy aquí.

Translation

(0:05) I am Carmen Navia, I am from the community of Tutunendo, from zone 1, I have 9 siblings,

(0:17) Within the 9 I am the youngest and there in that community of Tutunendo I finished my high school

(0:29) and then I came here to Quibdó to finish the last two years. When I finished then

(0:39) There in Tutunendo there was a lot of talk about Asia and there were community councils,

(0:46) It was not a community council but a local committee and my dad took me to those meetings a lot.

(0:53) and they talked about Asia, they talked about some territories, and in the 99s, well, to me, it seemed like

(1:01) I began to like what he said and he went out to committees a lot, I gradually joined

(1:09) the topic and from one moment to the next I got into the process, I got into the organizational process

(1:17) where, my life has changed a lot, in that time of '91 one ends, and these ideas,

(1:30) Sometimes financially I didn't have a way to continue college and from there I got into this

(1:37) process where he has taught me so many things, to see life differently, if I were not here

(1:46) In Cocomacia I believe that my life would be different because many opportunities were presented to me

(1:55) both good and bad too, then one was already getting to know the friends here in the

(2:05) organization that was different from the other friendships, the people who were not involved, well

(2:11) like in Asia and I became very interested in the defense of this territory seeing that we

(2:21) We are the ones who take care of the forest, we are the owners and as previously the companies came, they got involved

(2:31) to the communities without permission, they were taking all the wood, and in the case of my town there in Tutuniendo

(2:40) Also those companies, few paisas came to and they cut wood in the territory and nobody disagreed

(2:50) It was like, there was no law nor was there an authority to suspend it, so with what

(2:58) of the organization when we already got into the regulations because there was how to paralyze that and how

(3:07) We could defend that wood, right now things are very different

(3:16) Because we already have a law 70, we have regulations and we enforce our

(3:27) Right so others must respect us. I have been involved in this entire process for 17 years now and I have

(3:40) learned to strengthen myself to be a different person, I am still here because it is the only organization that

(3:52) I can be free, where my values, my rights, I learned to know them and respect them and I feel

(4:03) very good, it is my organization, I feel a lot of love for it, I feel that if I arrive here in Quibdó and I do not

(4:11) come here to this building it feels like I have not arrived here in Quibdó, so I feel a lot of love for this

(4:18) organization and also for the role of women, of being multipliers, of bringing a message to them,

(4:28) that they no longer continue in that role of being the lady of the house, we women also have the

(4:36) right to go out, to know, to make our own decisions, to come to meetings and

(4:45) Give our opinion, not just arrive and sit there but move forward, because if not,

(4:51) We're going backward, that's why I'm here.

Mariluz Moya

Mariluz es vocera de la comisión de género de Cocomacia, originaria de Puerto Salazar en Beté, zona cuatro del municipio Medio Atrato, resalta la importancia del empoderamiento femenino en las comunidades. Destaca los esfuerzos para involucrar a más mujeres en el proceso organizativo, superando barreras de timidez y roles de género tradicionales.

El relato destaca los logros obtenidos mediante la colaboración comunitaria, como la adquisición de una canoa para el transporte y la gestión de recursos para proyectos locales. Se subraya el papel activo de la narradora en la promoción del liderazgo femenino y la igualdad de género.

Se destaca el impacto positivo del activismo en la vida personal y familiar, incluida la educación de los hijos en la igualdad de género y la participación cívica. Se enfatiza el apoyo de la familia, incluido el esposo concejal, en el compromiso continuo con la comunidad y el proceso organizativo.

El relato transmite gratitud hacia la organización Cocomacia por brindar oportunidades de crecimiento personal y comunitario, así como un firme compromiso con el progreso y la equidad en la región del Medio Atrato.

TRANSCRIPCIÓN

(0:06) Vengo de la comunidad de Puerto Salazán, municipio de Medio Atrato, que es Beté, en la zona 4.

(0:18) Y en estos momentos me desempeño como vocera aquí en la Comisión de Género de Cocomacia,

(0:24) y soy del Comité Zonal.

(0:28) Y en estos momentos estamos luchando para que las mujeres se animen a este proceso,

(0:37) que necesitamos que haya más mujeres que hombres,

(0:41) porque siempre nosotras las mujeres nos quedamos por ser tímidas,

(0:45) y porque los obedecemos, nos metemos mucho a la ley de los maridos,

(0:51) y no podemos estar en esa ley ya de los maridos,

(0:54) sino que tenemos que hacer su vida como mujer que somos, y hacerlo valer como mujer.

(1:02) Lo eligieron en la comunidad de AME, que pertenece también a Medio Atrato,

(1:10) como Comité Zonal, y nosotros nos sentíamos muy recogidos,

(1:18) porque no teníamos recursos, o no tenemos recursos,

(1:21) pero en estos momentos, gracias a las comunidades de toda la zona, de las nueve zonas,

(1:27) que nos apoyaron a esa rifa que hicimos de un motor,

(1:32) y gracias a Dios esa rifa quedó en la Junta del Comité Zonal,

(1:37) y desde ahí, uno dependiendo, porque ahí ya pensamos en una canoa de nueve metros,

(1:45) la mandamos a hacer, y la comunidad de PUNE correspondió a dos millones de pesos,

(1:50) y nosotros colocamos dos millones quinientos,

(1:54) y ahí ya pensamos al alcalde del municipio de Medio Atrato,

(1:59) le llevamos dos millones de pesos para que él nos colaborara con un motor quince,

(2:05) ya el alcalde nos apoyó que sí, y ahora nuevamente estamos haciendo otra rifa

(2:10) de un plasma, un televisor plasma, para nosotros tener recursos

(2:16) para movilizarlos a las comunidades de la zona cuatro,

(2:21) que son catorce comunidades, para los que no lo tengan claro,

(2:26) y les digo a mis compañeras que se animen al proceso,

(2:33) que no se queden en las casas, que los hombres se sienten orgullosos

(2:37) cuando sus mujeres ya son unas líderes, que ya no les da temor de hablar

(2:42) en alguna parte, que se capaciten, que uno día por día tiene que ir tratando de mejorar, (2:50) no quedarse hacia atrás, ya esa de uno estar debajo del compañero, eso ya pasó.

(2:59) Yo en estos momentos me siento muy agradecida de la organización de Cocomacia,

(3:04) porque he despertado mucho, y le he dado mucho conocimiento a mis hijos también,

(3:12) y viven muy comprometidos con el estudio, porque ellos están en bachiller,

(3:18) pero sí a mis dos hijos hombres que tengo, les enseño que el género tiene que ser,

(3:24) que ellos también tienen que hacer oficio en la casa, lo mismo que hace una mujer,

(3:29) les enseño a mis hijos hombres, dos hijos hombres tengo, tengo cuatro hijas mujeres, (3:35) y yo pues hablo mucho con mis hijos, les pongo las cosas claras,

(3:39) para que ellos más adelante tengan una vida feliz, y no digan,

(3:44) mi mamá no los enseñó nada, y nosotros quedamos muy mal,

(3:51) como ese dialecto de nosotros que hablamos así, ellos son unos que me apoyan,

(3:56) cuando alguna gira que me llaman acá en Cocomacia, ellos me dicen,

(3:59) mamá váyase, váyase, en estos momentos yo estoy estudiando, estoy haciendo bachiller, (4:06) y cualquier cosa que me necesiten aquí en la organización, aquí me tienen,

(4:11) desde que esté con vida y salud, y mis hijos, mi madre, que es mi ser más querido,

(4:19) estamos para adelante, y el marido que tengo, él también me apoya, que salga,

(4:27) en estos momentos es concejal en el Medio Atrato,

(4:31) y tiene una relación muy buena ya con sus compañeros en el consejo,

(4:37) y con el alcalde también, y ahí estamos, y gracias.

TRANSCRIPTION

(0:06) I come from the community of Puerto Salazán, municipality of Medio Atrato, which is Beté, in zone 4.

(0:18) And right now I serve as spokesperson here at the Cocomacia Gender Commission, and I am from the Zonal Committee.

(0:28) And right now we are fighting for women to be encouraged in this process, that we need there to be more women than men,

(0:41) because we women always stay because we are shy, and because we obey them, we get very involved in the law of husbands,

(0:51) and we cannot be in that law of husbands anymore, but we have to live our lives as the women that we are, and make us count as women.

(1:02) It was elected in the AME community, which also belongs to Medio Atrato, as a Zonal Committee, and we felt very limited,

(1:18) because we did not have resources, or we do not have resources,

(1:21) but right now, thanks to the communities of the entire zone, of the nine zones, who supported us in that raffle we did for an engine,

(1:32) and thank God that raffle remained at the Zonal Committee Meeting, and from there, one depending, because there we already thought of a nine-meter canoe,

(1:45) We ordered it to be done, and the PUNE community reciprocated two million pesos, and we payed two million five hundred,

(1:54) and there we already think of the mayor of the municipality of Medio Atrato, we brought him two million pesos so that he could collaborate with us with a fifteen engine,

(2:05) The mayor already supported us, yes, and now we are doing another raffle again of a plasma, a plasma television, for us to have resources

(2:16) to mobilize them to the communities of zone four, which are fourteen communities, for those who are not clear,

(2:26) and I tell my colleagues to encourage the process, that they do not stay at home, that men feel proud

(2:37) When their women are already leaders, they are no longer afraid to speak

(2:42) somewhere, that they train, that one day by day has to try to improve, not stay behind, and that of being below one's partner, that is already over.

(2:59) At this moment I feel very grateful for the organization of Cocomacia, because I have awakened a lot, and I have taught to my children too,

(3:12) and they live very committed to studying, because they are in high school, but yes, I teach my two male children that gender has to be,

(3:24) that they also have to do work in the house, the same as a woman does,

(3:29) I teach my male children, I have two male children, I have four female daughters, and I speak a lot with my children, I make things clear to them,

(3:39) so that they may later have a happy life, and not say, my mother didn't teach us anything, and we were very bad,

(3:51) like that dialect of us who speak like that, they are some who support me,

(3:56) When some tour calls me here in Cocomacia, they tell me,

(3:59) Mom, go away, go away, right now I'm studying, I'm doing high school, and whatever they need me here in the organization, they have me here,

(4:11) As long as I am alive and healthy, and my children, my mother, who is my dearest being,

(4:19) We are moving forward, and the husband I have, he also supports me, let him go out,

(4:27) At the moment he is a councilor in Medio Atrato, and he already has a very good relationship with his colleagues on the council,

(4:37) and with the mayor too, and there we are, and thank you.

Ma. del Socorro Mosquera

El relato de vida de Maria del Socorro, nacida en 1953, refleja su valentía y perseverancia en medio de desafíos personales y sociales. A pesar de enfrentar la maternidad sola y separarse de su compañero, encuentra fuerza en su fe en Dios y el apoyo de la comunidad, especialmente de Cocomacia.

Destaca su habilidad para aprender y sobrevivir gracias a su destreza en las artesanías, así como su compromiso con el proceso organizativo y la lucha por la equidad de género. Subraya la importancia de que las mujeres conozcan y defiendan sus derechos, incluso en situaciones de desplazamiento, y valora las capacitaciones recibidas en este sentido.

Con 60 años de edad, sigue sintiendo el impulso de contribuir y apoyar a otras mujeres, reconociendo la necesidad continua de solidaridad y colaboración entre compañeras para superar los desafíos cotidianos. Su historia resalta la resiliencia y determinación de las mujeres en la búsqueda de una vida digna y justa.

TRANSCRIPTS

(0:00) Buenas tardes compañeras, aquí les traigo estas coplas de la ley que nos protege de la distinta violencia.

(0:20) Buenas tardes para todas las mujeres del área de influencia de Cocomacia,

(0:24) y por qué no decir para todas las mujeres de Colombia y del mundo que me escuchan,

(0:30) voy a contarles un poco lo que ha sido la historia de mi vida.

(0:34) Yo nací en el año 1953, fui una hija que mi mamá luchó conmigo su embarazo hasta que nací y me crié sola.

(0:48) Tuve siete hijos, he luchado con ellos sola porque no he tenido un compañero de tiempo completo para que me ayude con la familia.

(0:58) Pero gracias a Dios, con la ayuda de Dios y todas las compañeras que me han apoyado, he podido sacar un poco a mis hijos adelante.

(1:06) Yo soy una mujer que me organizé con mi compañero, pero en este momento estoy separada de él.

(1:15) Gracias a Dios, el apoyo que he recibido de muchas personas, especialmente aquí en la Cocomacia,

(1:21) que me han brindado mucho apoyo en cuanto a los trabajos y por el arte que he aprendido,

(1:28) porque yo gracias a Dios, Dios me ha dado una oportunidad de aprender a hacer muchas cosas, especialmente la artesanía.

(1:34) Y gracias a esa artesanía me ha ayudado a sobrevivir, que yo sé hacer muchas cosas y aparte de la artesanía,

(1:43) también mi mente la tengo despejada para aprender muchas cosas de lo que ha sido el proceso organizativo,

(1:49) que se ha llevado a muchas partes del mundo, se le ha compartido a muchas mujeres,

(1:54) y por eso yo espero que todas y cada una de las mujeres que han recibido estas capacitaciones

(1:59) que nosotras nos hemos dado frente a lo que ha sido el tema de equidad de género,

(2:04) lo que ha sido conocer nuestros derechos, que no sigan violando más nuestros derechos.

(2:10) Todas esas luchas que hemos tenido, espero que cada una de las mujeres que me están oyendo

(2:14) sepan analizar todas y cada una de estas propuestas que hemos trabajado con ellas,

(2:20) para que así nosotras podamos salir adelante.

(2:22) Porque a pesar del desplazamiento, hemos sabido sobrevivir con cada una de las cosas que aprendemos.

(2:29) Muchas cosas que nos enseñan, de pronto nosotros pensamos que eso no va a servir,

(2:34) pero nos sirve para defendernos después en esta situación como desplazadas.

(2:39) Tengo 60 años cumplidos, a pesar de esa edad que tengo, me siento con ánimo de seguir trabajando,

(2:45) de seguir aportando a cada una de las compañeras que necesiten mi apoyo,

(2:50) porque cada día que uno crece, cada día que uno anda,

(2:55) necesita aún más apoyo de cada una de las compañeras y compañeros para poder sobrevivir.

TRANSCRIPTS

(0:00) Good afternoon colleagues, here I bring you these verses of the law that protect us from different types of violence.

(0:20) Good afternoon to all the women in the area of influence of Cocomacia, and why not say for all the women in Colombia and the world who listen to me,

(0:30) I'm going to tell you a little about what the story of my life has been. I was born in 1953, I was a daughter whose mother fought with me during her pregnancy until I was born and raised alone.

(0:48) I had seven children, I have struggled with them alone because I have not had a full-time partner to help me with the family.

(0:58) But thank God, with the help of God and all the colleagues who have supported me, I have been able to help my children move forward a little.

(1:06) I am a woman who organized with my partner, but at this moment I am separated from him. Thank God, for the support I have received from many people, especially here in Cocomacia,

(1:21) who have given me a lot of support in terms of work and the art that I have learned, because I thank God, God has allowed me to learn to do many things, especially crafts.

(1:34) And thanks to that craftsmanship it has helped me survive because I know how to do many things and apart from craftsmanship, I also have a clear mind to learn many things about what the organizational process has been,

(1:49) that has been taken to many parts of the world, has been shared with many women, and that is why I hope that every one of the women who have received these trainings

(1:59) that we have faced what has been the issue of gender equality, what it has been like to know our rights, that they do not continue to violate our rights anymore.

(2:10) All those struggles that we have had, I hope that each of the women who are listening to me know how to analyze each one of these proposals that we have worked with, so that we can move forward.

(2:22) Because despite the displacement, we have managed to survive with each of the things we learn.

(2:29) Many things that they teach us, suddenly we think that that is not going to help, but it helps us to defend ourselves later in this situation as displaced people.

(2:39) I am 60 years old, despite my age, I feel like continuing to work, to continue contributing to each of the colleagues who need my support,

(2:50) because every day that one grows, every day that one walks, she needs even more support from each of her companions in order to survive.

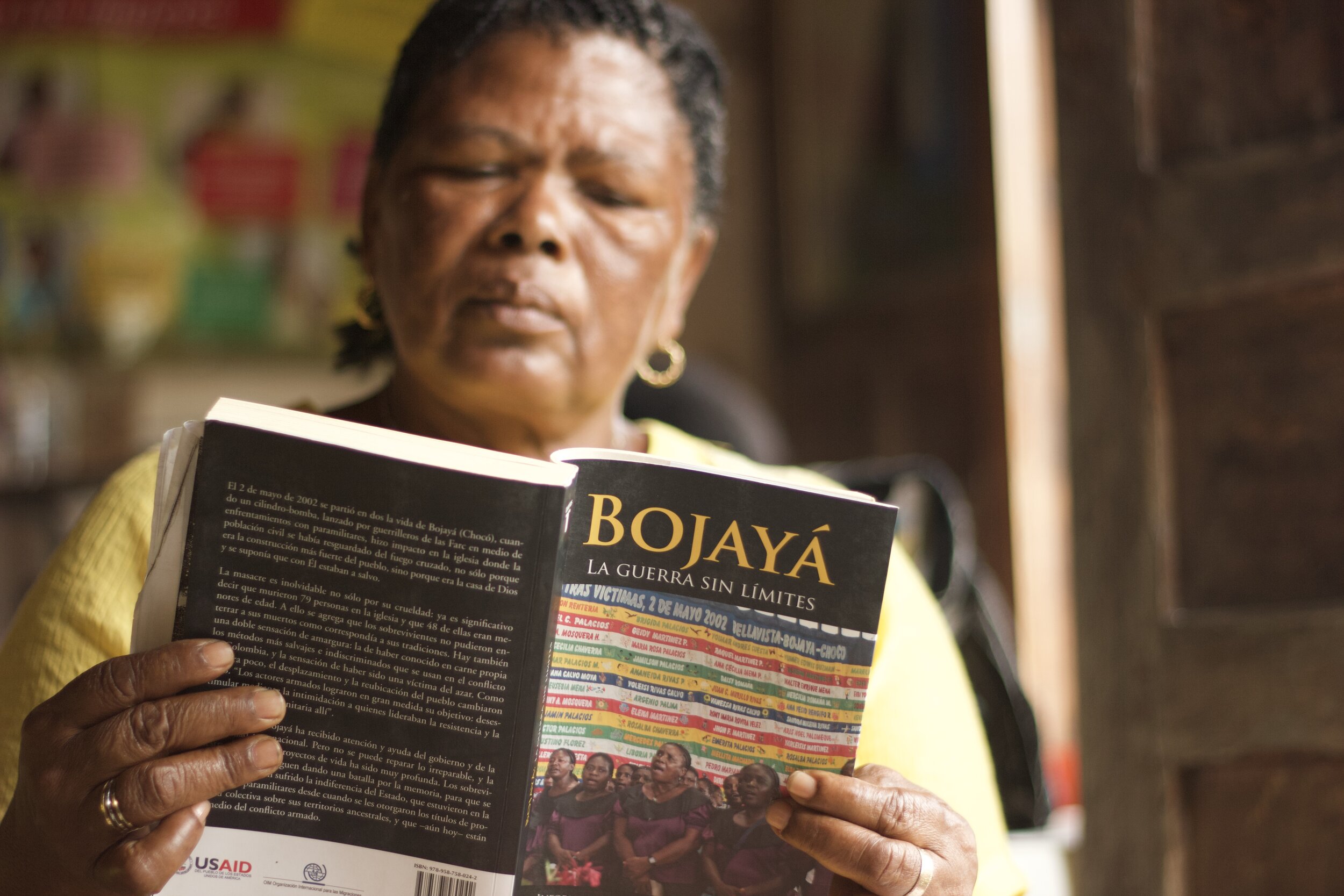

Miriam Moya

Esta es la historia de Miriam, quien se separó de su pareja hace más de una década y ha estado luchando para criar a sus hijos desde entonces. A pesar de sus esfuerzos, Miriam no ha podido conseguir una vivienda propia debido a las dificultades económicas que enfrenta, a pesar de poseer un terreno. Recientemente, le ofrecieron una vivienda en mal estado que pudo mejorar para habitar temporalmente, pero el propietario le indicó que deberá abandonarla porque su hijo necesita el lugar. Esto la ha sumido en la tristeza y la preocupación, especialmente porque en su comunidad los proyectos de vivienda benefician principalmente a aquellos que ya tienen propiedades. Miriam reflexiona sobre la falta de oportunidades laborales en su zona y la necesidad urgente de una vivienda estable para su bienestar y el de sus hijos. Además, menciona el historial de violencia y abuso por parte de su expareja, lo que la llevó a salir de su lugar de origen. Miriam busca apoyo y soluciones para mejorar su situación y encontrar un lugar seguro y estable para su familia.

TRANSCRIPCIÓN

(0:04) Hace más de 10 años, me separé del papá de mis hijos, no soy la misma. Si fuera un buen hombre, yo viviría con él.

(0:15) Y desde ese tiempo para acá, he venido luchando, luchando, que gracias a Dios, que ya la última, el próximo año va para la colegio.

(0:28) La otra está en la universidad, y los otros van al colegio. Pero, a pesar que he luchado, yo creo que por no tener mucho yo, la fuerza no me ha dado como tener una vivienda.

(0:46) Un lote sí tengo, un lote muy bonito, plano, pero no he tenido fuerza de como tener la vivienda.

(0:55) Y uno para construir una vivienda, uno no la construye con dos pesos. Porque un bulto de cemento nada más vale aquí 25, 26 mil pesos.

(1:07) El solar mío tiene 6 por 14 de fondo. Entonces yo me siento muy aburrida, porque no tengo vivienda.

(1:21) El año pasado, un señor me dio una vivienda a vivir. La vivienda estaba toda mala, no tenía piso, no tenía servicios, no tenía agua, nada.

(1:36) Bueno, y arreglamos que yo la fuera mejorando y viviera en ella. Y entre noches, cuando ya me fui de aquí a mi trabajo, me llenó el celular.

(1:50) Donde me dice que si no la termina de mejorar, según me va a sacar de la vivienda. La gente me decía, Miriam, usted está mejorando esa vivienda.

(2:05) Esa vivienda, cuando el dueño la vea bien buena, la saca de esa vivienda. Y yo le decía a la gente, no, de pronto no, porque él es mi paisano.

(2:16) Con mi papá eran familia, vale. Y verdad, ahora que ya la vivienda está así. Con piso, repellado bien buena, con servicios. Y mejor dicho, organizada.

(2:30) Hay cuatro tanques. Entonces él estuvo un día y yo creo que se entusiasmó de ver la vivienda. Y ahora ya me está diciendo que el hijo que vive en Bogotá,

(2:41) y que tal que se viene para Diciembre con la mujer y los hijos, y necesitan la vivienda.

(2:51) La gente dice que de pronto puede ser mentira, y no que, pues quiere sácarme de su vivienda. Para arrendala y ahí coger su plata.

(3:01) Yo ayer pasé el día llorándo, de verdad muy triste. Porque aquí en el Chocó, los proyectos llegan.

(3:11) Pero llegan para la gente que tiene. Ve allá en este barrio que yo vivo, un barrio desplazado. Él se llama el 2 de mayo, por la violencia que hubo en Bellavista.

(3:26) Lo colocaron el 2 de mayo. Ve, allá la mayoría de casas son de las profesoras, son de las enfermeras.

(3:35) Y las tienen arrendadas. Y a los que no tenemos, no salimos en esos proyectos. Entonces uno aquí, aquí en el Chocó, no hay empleo.

(3:49) Uno ganase, sí que unos 600.000 pesos. Ahorita yo aquí donde estoy, lo que me pagan es 400.000 pesos. Díganme, uno con tantos hijos estudiando.

(4:04) Pagando energía, que pagando cable, unas cosas. ¿Para qué le alcanzan 400.000 pesos? Viene uno más, viene prestando a muchas cosas.

(4:17) Entonces yo le decía a mi mamá, anoche menos de anoche. Y yo quería como, si me consiguiera un trabajo fuera del Chocó.

(4:29) Porque sin vivienda, yo no me siento bien. Y yo he pasado mucho trabajo, que yo pasé mucho trabajo con el papá de mis hijos.

(4:40) Ese tipo me cortó, me cortó aquí en la cabeza. Ese tipo me hacia a disparos. Vea, esto era una cosa de loco cuando se endiablaba por eso fue es que yo salí del pueblo.

(4:57) Y he sido paso de trabajo en trabajo hasta que Dios quiera que termine de criar los pelados. Los hijos míos por eso no les piden al Papa nada.

(5:09) Él es minero. Y ellos no te asoman donde él. Como ellos no tienen casi, ni la casa de ellos, del papá de ellos con la madrastra pues, es una casa muy bonita, bien elegante.

(5:25) Y tienen de todo. Entonces yo creo que eso él humilla a los pelaos y no les gusta que ellos vayan.

(5:32) ustedes que vienen a buscar, váyanse para su casa, váyanse, váyanse. Entonces yo les pregunto, ¿En qué me puede usted ayudar?

(5:43) A ver si yo salgo adelante, a ver si ellos me ayudan cómo hacer mi rancho

TRANSCRIPT

(0:04) More than 10 years ago, I separated from the father of my children, I am not the same. If he were a good man, I would live with him.

(0:15) And from that time until now, I have been fighting, fighting, thank God, that now the last one, next year I go to school.

(0:28) The other is at university, and the others go to school. But, although I have fought, I believe that because I do not have much of myself, the strength has not given me the means to have a home.

(0:46) I do have a lot, a very nice, flat lot, but I haven't had the strength to know how to have the home.

(0:55) And to build a house, one does not build it with two pesos. Because a lump of cement costs only 25, 26 thousand pesos here.

(1:07) My lot is 6 by 14 deep. So I feel very bored, because I don't have housing.

(1:21) Last year, a man gave me a house to live in. The house was all bad, it had no floor, it had no services, it had no water, nothing.

(1:36) Well, we arranged for me to improve it and live in it. And between nights, when I left here for work, he filled up my cell phone.

(1:50) Where he tells me that if he doesn't finish improving it, according to him he is going to kick me out of the house. People told me, Miriam, you are improving that home.

(2:05) That home, when the owner sees it as good, takes it out of that home. And I told people, no, not suddenly, because he is my countryman.

(2:16) With my dad they were family, okay. And true, now that the house is like this. With a very good floor, plastered, with services. And better said, organized.

(2:30) There are four tanks. So he was there one day and I think he was excited to see the house. And now he is already telling me that the son who lives in Bogotá,

(2:41) and what if he is coming in December with his wife and children, and they need housing.

(2:51) People say that it could suddenly be a lie, and not that because he wants to get me out of his house. To rent it and get your money there.

(3:01) Yesterday I spent the day crying, really very sad. Because here in Chocó, projects arrive.

(3:11) But they come for the people who have. Go there in this neighborhood that I live in, a displaced neighborhood. He is called on May 2, because of the violence that occurred in Bellavista.

(3:26) They placed it on May 2nd. See, most of the houses belong to the teachers, they belong to the nurses.

(3:35) And they have them rented. And those of us who don't have one, don't appear in those projects. So one here, here in Chocó, there is no job.

(3:49) One would win, yes, about 600,000 pesos. Right now where I am, what they pay me is 400,000 pesos. Tell me, one with so many children studying.

(4:04) Paying for energy, paying for cable, some things. What is 400,000 pesos enough for? One more is coming, it is lending itself to many things.

(4:17) So I told my mom, last night except last night. And I wanted, like, to get a job outside of Chocó.

(4:29) Because without housing, I don't feel good. And I have had a lot of work, I have had a lot of work with the father of my children.

(4:40) That guy cut me, he cut me here on the head. That guy was shooting at me. Look this

It was crazy when he became devilish, that's why I left the town.

(4:57) And I have been moving from job to job until God wants me to finish raising the peelers. That's why my children don't ask the Pope for anything.

(5:09) He is a miner. And they don't show you where he is. Since they hardly have anything, not even their father's house with their stepmother, well, it is a very nice, very elegant house.

(5:25) And they have everything. So I think that that humiliates the pelaos and they don't like them to go.

(5:32) You who come to search, go home, go, go. So I ask you, how can you help me?

(5:43) Let's see if I can get ahead, let's see if they help me how to make my house

Julia Mena

El relato de vida de Julia Mena es un testimonio de valentía, resiliencia y determinación en medio de desafíos personales y sociales. Aprendió de su cuñado, un médico tradicional, habilidades curativas que hoy aplica con sabiduría y humildad.