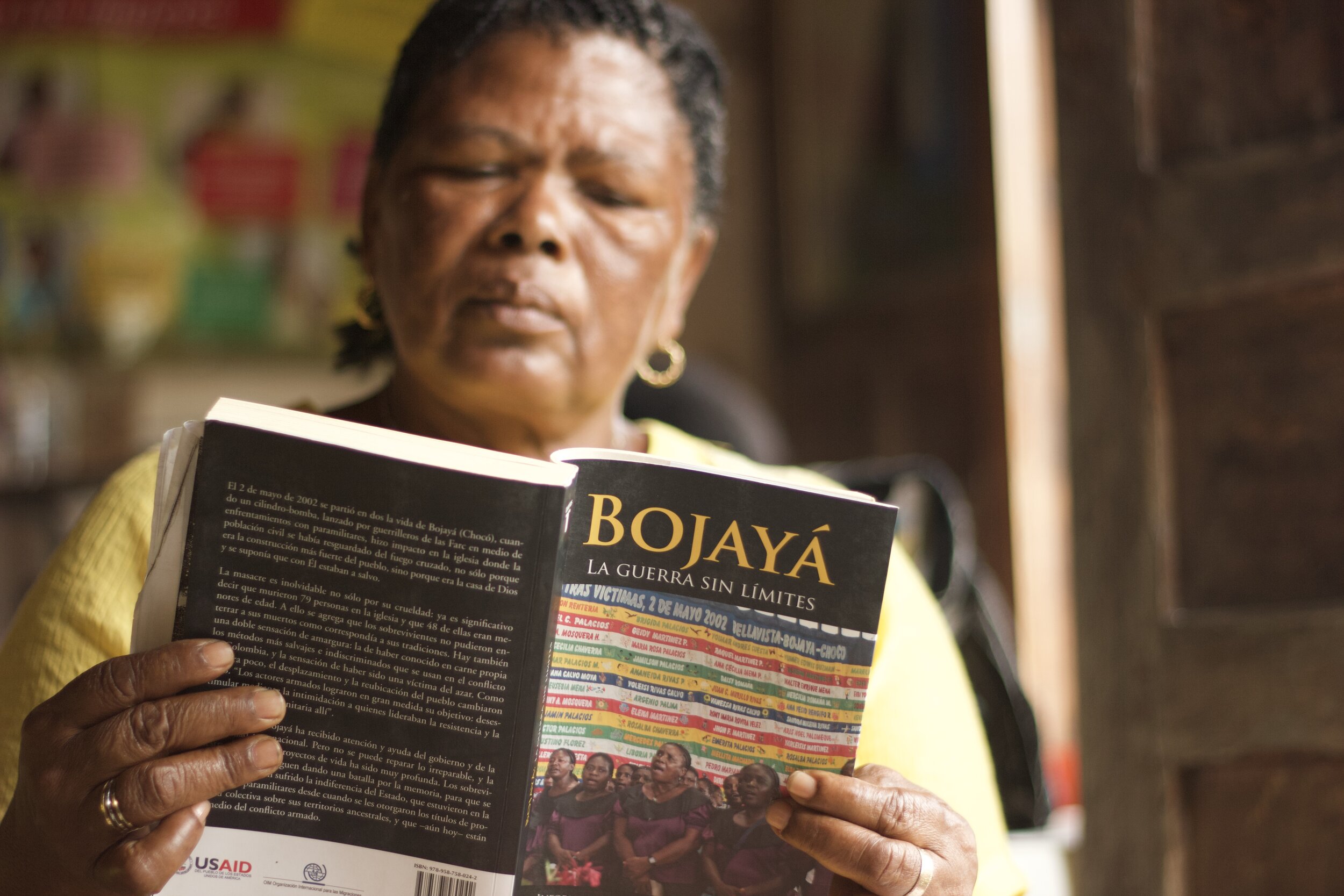

Ana Rosa Heredia

La vida de Ana Rosa Heredia Acosta es un testimonio de superación y lucha en medio de la adversidad. Nacida en una familia humilde en Bojayá, Chocó, Ana Rosa enfrentó desafíos desde una edad temprana. Su madre, una partera reconocida en la comunidad, y su padre, también partero, lucharon para criar a sus 14 hijos en circunstancias difíciles.

Desde joven, Ana Rosa enfrentó el acoso y la violencia de género, enfrentando situaciones traumáticas que la llevaron a huir de su pueblo natal. Trabajó en diversas ciudades del país, luchando por sobrevivir y buscando oportunidades para mejorar su vida y la de su familia.

A pesar de los obstáculos, Ana Rosa encontró fortaleza en su trabajo y en la comunidad. Se unió a la lucha por los derechos de las mujeres en el Chocó, desempeñando un papel activo en la organización comunitaria y la defensa de los derechos humanos.

Su historia es un recordatorio del poder de la resiliencia y la determinación en la búsqueda de una vida mejor. A través de su valentía y perseverancia, Ana Rosa ha inspirado a otros a enfrentar los desafíos con coraje y esperanza.

La historia de Ana Rosa

TRANSCRIPCIÓN

(0:07) Mi nombre es Ana Rosa Heredia Acuesta. Vengo de una comunidad muy humilde, yo pertenezco al municipio de Bojayá y soy de una familia humilde, pobre.

(0:24) Mi mamá era partera, mi papá también. Mi mamá tuvo, con mi papá tuvieron 14 hijos, 7 hombres y 7 mujeres.

(0:35) Se murieron algunos y apenas quedamos 7, se murieron otros 7. Y de esos 7 quedaron 3 hombres y 4 mujeres.

(0:46) Mi mamá antes de morir ya había partido como partera, había recibido 800 mil muchachos en el Atrato. Ya el hospital le reconocía sus pactos.

(1:02) Y pero desde chiquita yo fui muy gordita, amarillita y me perseguían mucho los hombres desde pequeña. Y llegó un señor a vivir en el pueblo y él siempre me acosaba.

(1:16) Aunque yo en ese tiempo no sabía que era acoso. Pero él siempre me acosaba, donde me veía, me molestaba, me molestaba.

(1:22) Entonces yo ya estaba grande, ya tenía 14 años. Y el señor, yo le decía a mi mamá que él me molestaba.

(1:32) Y mi mamá un día lo llamó y le dijo que yo siempre le contaba a ella que, ve yo acariciándola porque como es así gordita, ella cree que es por alguna cosa acariciándola.

(1:44) Y un día cuando ya yo tenía 16 años, ese mismo señor me mandó una carta. Porque antes se enamoraban con cartas.

(1:51) Me mandó una carta que se la contestara enseguida porque si no se iba a volar del pueblo. Entonces yo le mandé a decir que su mamá era la que tenía lápiz porque yo no tenía,

(2:02) que fuera donde su mamá. Y que hizo, vino y me dijo que esa palabra que yo le había dicho, él me castigaba.

(2:10) Y me hizo una parada, ¿qué hacía? Una parada. Y me cogió.

(2:15) Y me cogió. Apenas yo había hecho un quinto de escuela.

(2:21) En ese tiempo me hizo cosas para que yo no lo dejara. Entonces otro médico me hizo para desbaratarme la cosa.

(2:31) Que así que nunca la terminó de desbaratar y lo que él me hizo tampoco me lo acabaron de sacar.

(2:37) Y ya yo me largué a andar. Empecé a andar de pueblo en pueblo.

(2:43) Fui para Cartagena, de Cartagena me vine a Turbo. En Turbo me tocó trabajar en esas bananeras.

(2:50) Ya me tocó trabajar porque yo le cogí un odio al señor que no lo podía ver. Y andaba huyéndole.

(2:56) Me fui con una amiga, me llevó a Montería, una muchacha jovencita, me llevó a Montería. Y allá yo pasé mucho trabajo.

(3:04) Porque yo era negra y sus papás pues... Allá son chilapos negros pero yo no les caí bien. Y allá y sin tener cómo hacer el pasaje.

(3:12) Así que ella reunió y me dieron el pasaje y me vine para Turbo. De Turbo me vine a Medellín, la vida mía ha sido andar.

(3:19) Estuve en Medellín mucho tiempo trabajando como muchacha del servicio. De Medellín me pasé a Bogotá.

(3:28) Estuve trabajando en Bogotá, andaba con una señora y trabajé, y trabajé, y trabajé. Ya me vine aquí a mi Chocó otra vez.

(3:37) Y ya mi mamá, llegué de nuevo y bueno, hice una buena vida. Había una compañía madedera que desde ahí nació La Asia.

(3:45) Una compañía madera que daba mucha plata y allá yo me cogieron a trabajar ahí. Y yo empecé a cambiar y fui otra persona.

(3:52) Y ya fui mujer de fama, tuve muchos negocios. Sí, tuve muchos negocios y tenía motores y cosas.

(4:01) Y vendía ropa. Yo estuve en negocios grandes. Y tuve trabajadoras, mantenía de dos.

(4:09) Cuando ya vino la guerra que entró, la guerra, la violencia. Yo quedé así como estoy aquí.

(4:16) Me tocó salir de mi pueblo. A mí no me hicieron nada. Sino que el problema fue que en mi casa vivía una muchacha con su familia.

(4:25) Y había caído en la pipeta de Bojayá con todos los hijos. Y las cosas quedaron en mi casa. Y yo de ese miedo y ese guayabo me hizo volar.

(4:38) Salí volando. Existía La Asia, pero a mí no me gustaba. Y ya llegué aquí a Quibdó y empecé a ir a las reuniones y a las cosas y a las vainas.

(4:49) Y yo digo, ¿qué Asia? Yo tengo que ensayar cómo es La Asia. Si me gusta o no. Si no me gusta, pues bueno. Y me vine y me ofrecí.

(4:57) Que cuando necesitaran a alguien para un recorrido, alguna cosa, era yo. Estaba dispuesta. Estaba esta Justa en la junta de ellas.

(5:07) Y me dijo, bueno, no hay problema. Y ahí volví, me fui para abajo a recoger y que lo mío. Llegué allá y había habido una creciente.

(5:15) Y no me quedó nada. Todo se me había mojado. Todo se me había dañado y no traje nada. Y en eso bajaron ellos.

(5:21) Cuando bajaron, yo todavía estaba allá y los atendí muy bien. Y en mi casa, y bueno.

(5:27) Y ya yo tenía cosas de La Asia.

(5:30) Cuántos consejos comunitarios tenía y todo eso. Y a ellos les gustó mucho. Y ya me dijeron que me iban a traer.

(5:38) Y como a los ocho días de estudio me llamaron. Me vine aquí a trabajar. Y llegué como comisionada de autonomía.

(5:47) Éramos comisionadas de autonomía, en autonomía. Y ahí trabajé esos dos años. Cuando dio los tres años, ya Justa dijo

(5:58) que se dio la Asamblea de las Mujeres. Cuando se dio la Asamblea de las Mujeres,

(6:04) a mí allá en mi pueblo me sacaron como comisionada. Ya yo estaba acá.

(6:09) Pero que los comisionados que sacaron no trabajaron porque no tenían con qué ponerlos a trabajar.

(6:14) Entonces ya yo me quedé acá con Justa. Hicimos la área, nos pusimos y pusimos la área de mujeres.

(6:20) Apenas era María del Socorro, Justa y yo. Nosotras tres. Y empezamos la lucha. Pero yo me metí a lo logístico.

(6:31) Y Justa, María del Socorro con su tejido, su artesanía. Y Justa estaba en lo político, en lo político y lo social, en lo político y lo social.

(6:40) Y yo pues ni entendía de eso. Ni entendía de eso. Y cuando ya yo le fui cogiendo como, le fui poniendo cuidado a lo que ella hacía.

(6:49) Y me fui metiendo. Y me fui metiendo y ya me fui preocupando, me fui preocupando y le dije, bueno Justa, yo estoy dispuesta a ayudar en lo que sea.

(6:59) Dígame qué hay que hacer y aquí estoy. Y los cogimos y nos cogimos. Y verdad. La área de género. Nació la área de género.

(7:08) Y empezamos a dar talleres en las comunidades. Porque ya nos había venido una señora a capacitar. Entonces empezamos a dar talleres.

(7:17) Por diaconia y PCS. En las comunidades empezamos a hacer fortalecimiento a las mujeres. Porque decíamos, ¿por qué las mujeres no vienen a los eventos?

(7:28) Y ellas nos decían que era porque no tenían con quién dejar a sus hijos, porque los maridos no las dejaban.

(7:34) Y ya empezamos la lucha. Y empezamos la lucha. Y ya fuimos analizando mujeres. Y fuimos involucrando mujeres. Ya se nos terminó.

(7:45) Un proyecto que fue que nos dio diaconía se nos terminó. Después nos dieron otro proyecto y ahí fue que hicimos la escuela.

(7:55) Que trajimos dos personas por comunidad. Nosotras éramos las maestras. A nosotras nos capacitaban y a nosotras seguíamos, (8:05) los capacitamos a ellos. Y después se terminó la escuela a los dos años.Nos quedamos sin nada. Y ya Justa tenía una amiga que hacía flores.

(8:15) Y la trajimos aquí y empezamos a hacer flores.Empezamos a hacer flores. Y ya como hacíamos esas flores nos las compraban de tela.

(8:22) Con esas flores vendíamos unas flores y de esas comíamos.Nos repartíamos cada uno siempre así de esas y nos íbamos para su casa.

(8:29) Todos los días eso. Y entonces un día dijo Justa, bueno, ¿nosotras por qué? Nos pensamos en un restaurante.

(8:37) El restaurante nos sirve, nos da plata y comemos de ahí. Porque nosotros aquí no tenemos de qué subsistir. Y dije yo, yo estoy de acuerdo.

(8:46) Y vamos a buscar la plata, prestemos. Le digo que ese restaurante se colocaba así, vea. Vea esto que usted me ve, todo esto que usted me ve,

(8:55) esto así vea, vea esto negro y todo esto. Es de la quema, de la soya. Porque yo era la que sazonaba. Y entonces esa lucha y esa lucha y yo mis hijos.

(9:09) Vea, el hijo mío, la hija, terminó. Y apenas terminó, se fue para Bogotá. Porque como eran desplazados en el colegio,

(9:20) les decían que los desplazaban, que las cosas. Y entonces, a mí hija ya no le paró bola eso, pero yo voy aquí. Pero el niño sí, lo traumatizó.

(9:31) Llegó hasta noveno y no siguió más. Y recibían un papel en el suelo. Y ese papel quien lo desplazó ahí. Y eso era así, que los maltrataban.

(9:42) Entonces él de eso, de ese maltrato, no quiso terminar. Y se quedó así sin estudiar. Yo estoy por ponerle una psicóloga para ver qué es lo que él,

(9:54) ese trauma que tiene, de qué será. Sería por lo de la pipeta. Porque desde allá él estaba de 14 años cuando eso.

(10:01) Y eso a la gente como corría como loco. Yo digo que a él le quedó ese trauma. Y ha sido una lucha.

(10:10) Yo llegué a este pueblo y ha sido luchar y luchar. Lo que uno se gana aquí no es tan suficiente.

(10:16) Sí le sirve a uno, pero no es tan suficiente. Y el papá de mi hijo me abandonó. Se largó.

(10:28) Para que yo no lo siguiera, vendió todo lo que tenía. Y aquí se fue a vivir a Cali. Y yo me quedé luchando.

TRANSCRIPT

(0:07) My name is Ana Rosa Heredia Acuesta. I come from a very humble community, I belong to the municipality of Bojayá and I am from a humble, poor family.

(0:24) My mom was a midwife, my dad too. My mother had with my father 14 children, 7 men and 7 women.

(0:35) Some died and there were only 7 of us left, another 7 died. Of those 7, 3 men and 4 women remained.

(0:46) Before my mother died, she had already left as a midwife, she had received 800 thousand boys in the Atrato. The hospital already recognized her pacts.

(1:02) And but since I was little I was very chubby, yellow and men chased me a lot since I was little. And a man came to live in the town and he always harassed me.

(1:16) Although at that time I didn't know that he was bullying. But he always harassed me, wherever he saw me, he bothered me, he bothered me.

(1:22) Then I was already grown up, I was already 14 years old. And the man, I told my mother that he bothered me.

(1:32) And one day my mother called him and told him that I always told her that, I see me caressing her because since she is chubby like that, she believes that it is because of something that I caress her.

(1:44) And one day when I was already 16 years old, that same man sent me a letter. Because before they fell in love with letters.

(1:51) He sent me a letter to answer it right away because if not he was going to leave town. So I sent him to tell him that his mother was the one who had a pencil because I didn't have one,

(2:02) to go to his mother. And what she did, she came and told me that that word that I had said to him, he punished me.

(2:10) And he stopped me, what was he doing? One stop. And he caught me.

(2:15) And he caught me. I had barely completed a fifth of school.

(2:21) During that time he did things to me so that I wouldn't leave him. Then another doctor did me to break things up for me.

(2:31) So he never finished destroying it and what he did to me they didn't finish taking from me either.

(2:37) And I started walking. I started walking from town to town.

(2:43) I went to Cartagena, and from Cartagena I came to Turbo. In Turbo I had to work in those banana plantations.

(2:50) He Now I had to work because I hated the man who couldn't see him. And he was running away from him.

(2:56) I went with a friend, he took me to Montería, a young girl, he took me to Montería. And there I spent a lot of work.

(3:04) Because I was black and their parents, well... There they are black chilapos but they didn't like me. And there and without having how to make the passage.

(3:12) So she got together and they gave me the ticket and I came to Turbo. From Turbo I came to Medellín, my life has been walking.

(3:19) I was in Medellín for a long time working as a service girl. From Medellín I went to Bogotá.

(3:28) I was working in Bogotá, I was with a woman and I worked, and I worked, and I worked. I already came here to my Chocó again.

(3:37) And now my mom, I arrived again and well, I made a good life. There was a lumber company that from there La Asia was born.

(3:45) A wood company that gave a lot of money and they hired me to work there. And I started to change and I was a different person.

(3:52) And I was already a woman of fame, I had many businesses. Yes, I had a lot of businesses and I had engines and things.

(4:01) And he sold clothes. I was in big businesses. And I had workers, I supported two.

(4:09) When the war came, the war, the violence. I stayed like this as I am here.

(4:16) I had to leave my town. They didn't do anything to me. But the problem was that a girl lived in my house with her family.

She (4:25) And she had fallen into the pipette of Bojayá with all her children. And the things stayed in my house. And that fear and that guava tree made me fly.

(4:38) I flew away. La Asia existed, but I didn't like it. And I arrived here in Quibdó and started going to meetings and things and things.

(4:49) And I say, what Asia? I have to rehearse what Asia is like. Whether I like it or not. If I don't like it, fine. And I came and offered myself.

(4:57) That when they needed someone for a tour, something, it was me. Was willing. This Justa was in their meeting.

(5:07) And she told me, well, no problem. And there I came back, I went down to pick up what was mine. I got there and there had been a flood.

(5:15) And I had nothing left. Everything had gotten wet. Everything had been damaged and I didn't bring anything. And that's when they went down.

(5:21) When they came down, I was still there and I took care of them very well. And in my house, and well.

(5:27) And I already had things from Asia.

(5:30) How many community councils he had and all that. And they liked it a lot. And they already told me that they were going to bring me.

(5:38) And about eight days into studying they called me. I came here to work. And I arrived as autonomy commissioner.

(5:47) We were commissioners of autonomy, in autonomy. And I worked there for those two years. When she turned three years old, Justa already said

(5:58) that the Women's Assembly took place. When the Women's Assembly took place,

(6:04) They took me out as a commissioner there in my town. I was already here.

(6:09) But the commissioners they brought out did not work because they did not have anything to put them to work with.

(6:14) So I stayed here with Justa. We made the area, we set up and set up the women's area.

(6:20) It was just María del Socorro, Justa and me. The three of us. And we started the fight. But I got into the logistics.

(6:31) And Justa, María del Socorro with her weaving, her craftsmanship. And Justa was in the political, in the political and the social, in the political and the social.

(6:40) And I didn't even understand that. I didn't even understand that. And when I got to grips with her, I began to pay attention to what she did.

(6:49) And I got into it. And I began to get involved and I began to worry, I began to worry and I told him, well Justa, I am willing to help in any way.

(6:59) Tell me what needs to be done and here I am. And we took them and we took each other. And true. The gender area. The gender area was born.

(7:08) And we started giving workshops in the communities. Because a lady had already come to train us. Then we started giving workshops.

(7:17) For diakonia and PCS. In the communities, we began to strengthen women. Because we said, why don't women come to the events?

(7:28) And they told us that it was because they had no one to leave their children with because their husbands did not leave them.

(7:34) And we already started the fight. And we started the fight. And we were already analyzing women. And we were involving women. We're already done.

(7:45) A project that gave us diakonia has ended. Then they gave us another project and that's when we did school.

(7:55) That we brought two people per community. We were the teachers. They trained us and we followed,

(8:05) We train them. And then school ended after two years. We were left with nothing. And Justa already had a friend who made flowers.

(8:15) And we brought her here and we started making flowers. We started making flowers. And since we made those flowers, they bought them made of fabric.

(8:22) With those flowers we sold some flowers and we ate those. We each always shared those flowers and we went to her house.

(8:29) Every day that. And then one day Justa said, well, why us? We thought about a restaurant.

(8:37) The restaurant serves us, gives us money and we eat from there. Because here we have nothing to survive on. And I said, I agree.

(8:46) And we are going to look for the money, let's lend. I tell you that that restaurant was positioned like this, see. See this that you see me, all this that you see me,

(8:55) See this, see this black thing and all this. It's from burning, from soybeans. Because I was the one who seasoned it. Then the struggle and struggle, my kids and I

(9:09) See, my son, the daughter, is done. And as soon as she finished, she left for Bogotá. Because since they were displaced at school,

(9:20) They told them that they were displaced, that things. And then, my daughter couldn't stop that, but here I go. But the boy did, she traumatized him.

(9:31) He got to ninth and didn't go any further. And they received a piece of paper on the floor. And whoever moved that role there. And that was how they were mistreated.

(9:42) So he didn't want to end that, that abuse. And he was left without studying. I'm about to get him a psychologist to see what he,

(9:54) that trauma that he has, of what he will be like. It would be because of the pipette. Because from there he was 14 years old when that happened.

(10:01) And that made people like him run like crazy. I say that he was left with that trauma. And it has been a struggle.

(10:10) I came to this town and it has been fighting and fighting. What one earns here is not enough.

(10:16) Yes, it helps one, but it is not enough. And my son's father abandoned me. He took off.

(10:28) So that I would not follow him, he sold everything he had. And here he went to live in Cali. And I was left fighting.